Lin-Manuel Miranda's Unknown Neighbor

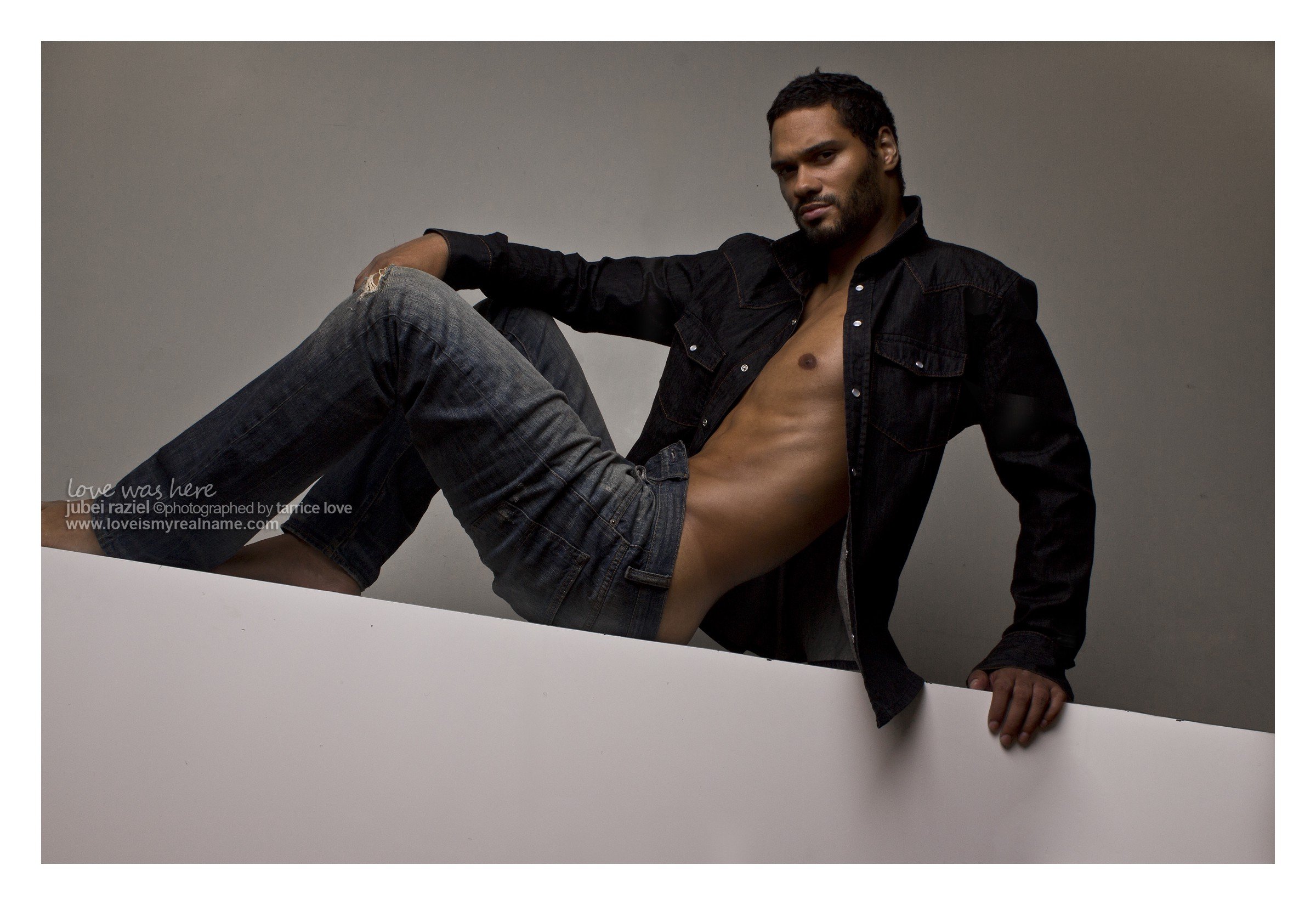

Photographed by Jubei Raziel

It’s late 2016, and I’m lying across my parent’s couch like a lethargic czar fighting post-meal drowsiness when a documentary about some Broadway show begins to air on the television. I rarely — if ever — watch PBS, but I’m too lazy to get up and change the channel to whatever sports game is playing. Hamilton’s America is the name of the feature, and it’s about the development of the hit show Hamilton through its creator, Lin-Manuel Miranda. His name doesn’t resonate but the documentary seemed intriguing enough; I haven’t a clue how Broadway shows are produced. If only the TV remote was closer.

My mom walks in, glances at the screen, then asks, “Oh, you remember Lin?” as if I had intentionally tuned in to watch because of him. My thoughts slog trying to figure out who the hell this guy was, also, how my mom knew him. With the on-going threat of postprandial somnolence, I come up empty.

She impatiently blurts out, “He was your neighbor, you know…that kid next door.”

I grew up on a fairly secluded street in Northern Manhattan where my dad was the superintendent of the building our family lived. My siblings and I harmonized with the neighborhood the way most kids would in small town America. Childhood ingredients included stick-ball, rummaging through the library for adventurous reads, Nintendo, little league baseball, climbing trees, and hanging out at the ice cream parlor playing arcades. Most of Inwood’s community of kids attended the same schools and churches, so, many of us knew each other, including our families. In retrospect, adolescence was magical because of how quaint it all seemed. However, what I couldn’t figure out for the life of me was why I failed to recall my own neighbor.

Sunset from La Marina in Inwood. Photographed by Jubei Raziel

I lived next door to Lin-Manuel Miranda, literally. He was that strange quiet kid who wore unassuming attire and was never without headphones. He’d walk to the beat of whatever he was listening to in a way that kept most of us from paying him any mind. My mom occasionally nudged me to become friends with him, but I felt uncomfortable approaching someone who seemed so disinterested with the world around. Lin would stroll right past my bedroom window after school every day like clockwork. I never saw him elsewhere, aside from entering or leaving the library. He never played ball or hung out with the guys from the neighborhood. It’s no wonder why I had difficulty placing him.

Nevertheless, I remember Lin’s dad, Luis. He was a kind neighbor who’d give a warm smile or a hello whenever he saw me cleaning the front of the building. It puzzled me why he parked more on the street than his driveway. The Miranda family lived in a house — a Manhattan rarity. I remember being envious of that because our family of five lived in a small two-bedroom apartment (quintessential living for Latinos in New York City). I recall Lin’s mom, Luz-Towns, who carried a unique calm I found peculiar because Puerto Rican women are known to be a bit...rambunctious (Sorry, mom). I had no idea she was a doctor until years later. Lin’s babysitter I frequently saw, and his grandmother and aunt visited regularly. Then, there was Lin’s sister, Luz, who I saw the least.

Funny enough, the Miranda’s backyard and ours were only separated by a couple scalable fences. I’d often jump into their yard to retrieve various balls my friends and I had accidentally hit or kicked too hard. I don’t think the Miranda family minded or noticed. They never really used it. During snowstorms my brother and I would shovel out a path from the front of our building down to the front of their house to minimize slips and falls for tenants heading to and from work. My brother even took some of his high school graduation pictures in front of the Miranda’s house because it was a better backdrop than our building entrance.

My mom talks with long-time family friend Edgar, another iconic Inwood superintendent. He used to block off the street so neighborhood kids could play. Lin was friends with his son, Richie. I played basketball with his other son, Edgar Jr.

My mom knew of the Mirandas and occasionally spoke with Luis. I reckon it was their Puerto Rican connection (We’re friendly like that). They had a mutual friend, Euclid Mejia, who was the principal of the High School I attended and where my mom worked (George Washington). Like me, Lin ended up taking his SAT there, but we never said hi to one another. I doubt he even knew of my existence. Talk about being so close yet so far.

I’m sitting up on the couch showing no signs of having “The Itis” watching Hamilton’s America in disbelief. My neighbor went on to become something extraordinary.

Curiously, I reach out to my sister and ask if she remembers Lin or ever spoke to him. She responds with, “That weird kid who never said anything to anyone?” I laugh but had to see if either of my siblings (my brother doesn’t remember Lin at all) might have possibly crossed paths with Lin at some point. But nope, never. Hamilton’s America is intriguing. A shot of Lin walking down our childhood street floods my mind with nostalgia. I shake my head when the screen shows Hamilton’s launch party because a close friend of mine, Kevin, was there; The company he worked for produced the event.

It’s all romantic and thrilling, yet poignant, because for someone I would see every day, Lin and I remained worlds apart despite living just feet from each other. Both of us being the same age and becoming creative writers and actors (though my career is focused on writing and photography now) just makes it all the more outlandish. I guess my mom suspected we would’ve been great friends. Would’ve, could’ve, should’ve. I refuse to judge my younger self for never connecting with Lin. I loved my childhood. Still, one can’t help but wonder, what if?

Remarkably, I see Lin and his dad every now and then because we all traverse the same areas after all this time. But the New York in me keeps things moving without ever approaching them. It’s not like I would know what to say aside from a neighborly “Hi” anyway.

Our home street. Hey Lin, remember when they removed the benches because they attracted too many hoodlums at night?

Soon after watching Hamilton’s America, I share how I grew up next to Lin-Manuel on Twitter. It was my way of pointing out that those striving to elevate their careers or are looking for their “big break” may be searching too far; We typically pursue opportunities from people of status, like celebrities and the wealthy, while ignoring the ones we see every day. The reality could be that the success we eagerly seek lies in simply exploring those around us and connecting with them.

It was humbling to have Lin-Manuel and his dad follow me on Twitter, though, it didn’t last long.

I encourage everyone to consider closing the gaps between themselves and those nearby. Embarking on the great adventure of discovering neighbors is a catalyst to brilliant living.

I didn’t expect my Tweet to be so well-received, let alone, read. Luis responded first with, “Say hello to your mother for me.” Then, Lin replied playfully, leading to a ton of likes, retweets, and new followers. It felt wondrous that people found value in what I deemed a trifling account of how close yet far two individuals can be without ever knowing each other. But that forging relationships with those who live close could turn out to be the most significant ones we have in life.

But what if Luis wanted to catch-up with my mom and I? Or, if Lin asked to actually meet up? Maybe this fleeting attention could somehow translate into something for my anemic career. Maybe someone might actually visit my website, or, perhaps I’ll get a job offer that would really advance things for me. Will I finally make headway as a writer? My mind raced with uncertainties of hope. I held my breath and told myself I will make the most of whatever happens with this virality. Did I successfully close the space between my childhood neighbor and I?

Photographed by Jubei Raziel

The most incredible thing happened to my life since sharing that tweet and article; Absolutely nothing.

I’m covertly hanging out at one of Columbia University’s graduation celebrations with a friend of mine uptown Manhattan. I don’t actually attend Columbia, my friend, Likun, does. She usually invites me to the campus study areas mindful that the only thing I seek more than working on my novel is the quiet I desperately need to do so. Admittedly, it has been nothing short of wonderful escaping my noisy neighborhood whenever possible, so, why not crash a graduation celebration as well?

I help myself to some catered food and beverages that were laid out before blending into crowds of proud families and happy graduates, though, I limit my interactions to only the people Likun knew, and mostly listen. Among the exchange of humor, exciting future plans, and stories of struggle from past semesters, I privately time travel. Let’s journey together...

Photographed by Jubei Raziel

I’m in North Florida living in a halfway house, the middle of nowhere. It’s 3 A.M. and a freight train infinitely snails just beyond my window. I can’t sleep. The air conditioner is ice skating uphill against the Southern heat. My surrounding occupants includes a heroin addict — attempting another recovery — and a cross-dressing hobo. The kind you only see in bad Hollywood films.

Just a couple weeks earlier, I was home in NYC asking my dad if he could help pay for college. What I recall from that numbing conversation was, “I’m not giving you a dime...” in the tune of some parsimonious pitch. Bitterness swelled, knowing he paid for both my brother and sister’s college tuition. It’s not my fault they were irresponsible students and never graduated. I was High School valedictorian, I guess that didn’t count for much. As it were, I was sleeping on a basement floor on a thrown-out mattress my father collected. He didn’t want me living with him in his two-bedroom two- bathroom apartment in the Bronx, so, he pushed me out. Either he couldn’t deal with my mom leaving him and wanted to be alone, or, he hated me. I couldn’t tell which. He hardly communicates and was always difficult to read.

With my brother away in the military, my sister living the married life in South Carolina, and my mom somewhere unknown, the only option for me was to secretly stay in one of the storage rooms in the building basement.

Being the superintendent, my dad knew it was illegal. He didn’t care. There was no kitchen, bathroom, or any running water in the dingy humid space, just a couple of barred-up windows covered with black garbage bags, and old junk everywhere. I couldn’t tell if it was day or night whenever in there, but at least I had an overhead florescent light with a pull-string switch. The ceiling was a mosaic of gaps and cracks; The floor, weathered concrete.

Next to my mattress was a small tube television I had my Sega Dreamcast hooked up to. I loved that console. Whenever I needed to use the restroom, I was told to use the one in the laundry room, but it was on the lobby floor and often locked. I guess the building janitor considered it his own. Nevertheless, I quickly learned how to dismantle and re-attach the lock’s latch with tools I found lying around. Things became more challenging when my dad urged me to never use the restroom while tenants were around. He didn’t want to risk losing his job. The good news was that I discovered an open drainpipe lying underneath a rusted metal cover while figuring out where all the water bugs were coming from. I’d lift it to pee into the dark abyss routinely. Putrid smell aside, the space was quiet. I liked that. It was occasionally disrupted by mice scrounging about for food at night, but otherwise peaceful.

Photographed by Jubei Raziel

It was so humiliating living under those conditions no matter how much I tried making it feel like a home. Escaping New York inevitably became the ultimate dream; Figuring a way out of poverty and depression consumed my mind. I’d regularly visit quiet spots along the Hudson River to remind myself life was worth fighting for. My parents weren’t going to help. Hell, my dad regularly ate in front of me and never offered. Countless days I’d go hungry, and drank straight from the laundry room faucet to fight it off. It was painful sleeping starved, but I got used to it. Every once in a while, I’d luck out with a meal at a friend’s place. I had to consciously prevent myself from overeating to avoid judgement; I simply never knew when my next meal was going to be. I needed a solution. How can I turn things around?

Thinking back, venturesome moments like the times I would sit on the outside ledge of the last train car to serenade the moon as I headed back home rekindled my desire to do something great with my life...even if I secretly felt it was never going to happen.

I began researching out-of-state colleges at a local library. Advancing my education was going to be the golden ticket out of my affliction. After meticulous probing, I found a community college in Florida I thought was perfect. It had warm weather, palm trees, and accessibility to beautiful beaches: The epitome of what dreams are made of. Nothing was keeping me in New York aside from an anemic modeling career. The devastating effects of September 11th were still lingering, leaving the advertising and modeling industries decimated and nearly all models unemployed. Not that being an ethnic introvert with Aspergers was actually netting me jobs.

FORD Models couldn’t solve how to market me. I hardly worked. When I did, it was pro-bono in efforts to build my portfolio. I was hopping trains to go to castings. During evenings, I’d serve drinks to celebrities at exclusive events for a catering company that occasionally hired me while privately figuring out how I was going to make it back to my mattress on the basement floor.

I promptly registered with the Florida college, begged around for enough money to purchase a one-way ticket, and set off for an adventure of a lifetime. I got my adventure. Just not the one I imagined.

The results of my college entrance exam determined that my reading comprehension and writing skills were graduate level but my math and science were grade school. Damn, remedial courses; Time and money for no credit. None of it matter though. In the end, I never took a single class. The financial aid paperwork I thoroughly submitted wasn’t approved, or, didn’t clear, due to some administrative issue that wasn’t made understandable to me. I had no money to fully cover the cost of classes, something the school demanded in advance to begin the semester. Despite my sincerest efforts, no help was offered on behalf of the college. This also meant I had no place to stay.

I desperately contacted the only person I thought could help me over a campus pay phone. A few quarters later, I was relieved to hear they found someone—who knew someone, that could arrange a place for me to stay while I sort out the college situation. That place? A halfway house.

The “friend of a friend” turned out to be a pastor who recently began a ministry aimed towards helping drug addicts and prostitutes reclaim their lives. His latest investment: Purchasing a broken-down motel where both addicts and prostitutes ran prevalent. He planned on converting it into some religious rehab center. And I was its newest resident.

As I listen to Columbia University’s latest graduates share their rich plans of world travel and new business ventures, envy fills me. I push it down with sushi and soda. My first attempt at college failed, along with all the others subsequently. But back to our journey...

Inside one of Columbia University’s study areas with Likun (seen). Photographed by Jubei Raziel

I felt darker, reluctant to return to the place I had to sneak through just to take a piss, but there was still fight in me. I’m a New Yorker, built tough. We figure shit out. After all, great stories are made from hard challenges, right? I should’ve never left the mice.

My immediate problem was that the halfway house stood too far from where I needed to be, and, there was no accessible transportation. I had to find a place to live and work close enough to the college. If I can survive a few months, I could attend classes the following semester. It’d grant plenty of time to sort out financial aid or some payment plan for tuition. I spoke to the pastor about my idea over the phone. After he muttered something about not being my chauffeur, he somewhat agreed to take me to the nearest town whenever time allowed. Till then, I had to stay put.

Meals were given on the premises, served in what looked like an abandoned shed. The ministry director confessed that what they offered was donated canned foods likely expired. he added it was something I ought to be grateful for.

The first time around, I refused to eat what was served and walked a couple miles along the nearest highway to the closest rest area. To my sweaty joy I discovered a Popeyes, to my dread, discrimenation. I quickly placed an order for chicken, fries, and a biscuit, but a police officer arrived with an attack dog threatening to jail me if I didn’t immediately leave the area after receiving my food. I can only reckon “my kind” wasn’t appreciated there. Upon returning to the halfway house, I was reprimanded for leaving. It was against the rules to do so. I had no idea. Even so, I wasn’t there for rehab or religion. Unfortunately, it appeared I was the only one who knew that. Thereafter, I reluctantly ate canned food with everyone else. It tasted worse than it smelled.

It’s 3 A.M. and a freight train infinitely snails just beyond my window. I can’t sleep against the rhythmic click-clack of freight cars rolling by. The air conditioner is ice skating uphill against the Southern heat. My surrounding occupants includes a heroin addict — attempting another recovery — and a cross-dressing hobo. The kind you only see in bad Hollywood films. I eventually succumb to the exhausting weight of anxiety and fall asleep. However, at 6 A.M. I’m jolted awake...to begin work. Disoriented, I asked why. The director said that as long as I remained, I needed to earn my stay. What? Before long, I was standing breathless and sweaty, garden hoe in hand, sporting blisters under a hot sun. Mealtime came again. This time the flavor was salty cardboard. I battled it with cheap cola. The following morning, I respectfully declined to work, clarifying my reason for being there, attempting to rectify the misunderstanding of my presence. The director phoned the pastor — who later showed up heated. He commands me to pack all my belongings. He was going to take me elsewhere.

I was thrilled to relocate to a town near the college. There was even accessible public transportation and places for possible employment. It came with a caveat though. I had to live in a shelter designed for homeless ex-convicts. This is where the pastor dumped me. He was friends with the owner and made it clear I was to be treated no different than anyone else. I never saw the pastor again. That first night is forever branded into my memory. I was assigned to a short bunk over a man who slept with a knife underneath his pillow. No position of comfort could be found on the decrepit 4-inch- thick mattress. My feet stuck out off the end. Worse, I laid a few feet from the only bathroom shared by the forty or so men surrounding me.

I fought back tears of anger and shame. A red light constantly buzzed above the bathroom door throughout the night. It penetrated my eyelids. Whenever my eyes opened, the haunting red glowed everywhere reminding me I was in hell. Still, it didn’t bother me as much as the stench emerging from behind the creaky door. It hit me like ocean waves. I resisted the urge to vomit repeatedly.

My brother would send a picture whenever he could to let me know he was still alive. (Undisclosed location in Iraq)

Thoughts of my brother touring in Iraq and my sister surviving her failing marriage filled my head. I missed my niece. She’d fall asleep on my stomach as I watched sports back when my sister lived in New York and let me babysit. Once again, I succumb to the weight of mental and emotional exhaustion, fantasizing about the peace I shared with the mice on the basement floor back in the Bronx.

Without missing a beat, I was awoken at 5:30 A.M. Not to work this time, but for group bible study and some more canned food. I wasn’t allowed to go back to sleep either. Shelter rules explicitly expressed that everyone had to go to their job or actively search for work during the day. So, I spent most my time sitting in what looked like a prison yard out back with a score of other unemployed ex-felons. There was one banged up basketball rim, no ball. We were also caged in by a tall fence with a side entrance chained locked. I’m too mortified to mention my public showering experience.

I had little money left, and without much hesitation, I spend the last of it purchasing a bus ticket to Austin, Texas, still refusing to return to New York. I had friends living there who would take care of me. Till this day I feel indebted for the love and kindness they showed. After some months of various unsuccessful attempts at both school and work, I ultimately returned to New York, and crashed with my mom and her girlfriend. I slept on the rug next to their bed for the next year or so. I was home.

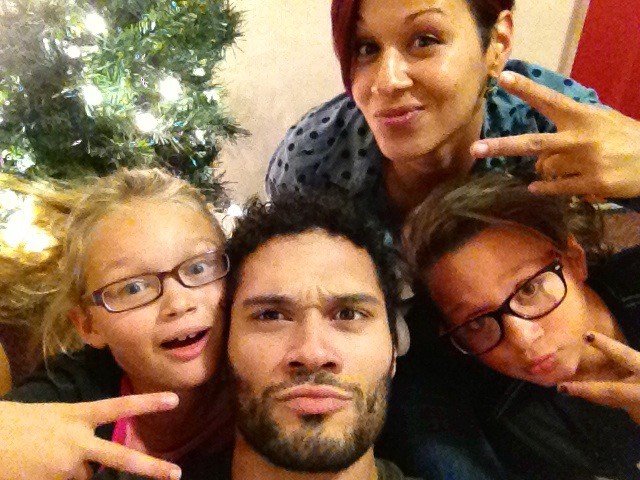

My sister and nieces on a memorable Thanksgiving.

Everyone assumes I’m a medical student, something I rather enjoy. I only admit to working on a novel once or twice if the conversation goes there, otherwise, I play along as a graduate. I feel a sensation of esteem unlike anything I’ve experienced before. I’m validated, respected...accomplished. Imagination flashes to what life could’ve been if I had been raised in a privileged home, had parents with notable careers who unconditionally supported and believed in me. Just then, something profound strikes me.

When I shared how I grew up next to Lin-Manuel Miranda, I wasn’t aware of what made me envious of him.

Sure, I already thought highly of his family, but there was a sophistication of unity, love and support between them that was trascending. I doubt Lin hung out till 4 A.M. playing ball in Van Cortland Park, or listened to rap on Post Avenue with drug dealers talking street politics. I doubt Lin ever had to sleep in a subway station or on a park bench, or steal cans of tuna from friends’ kitchen cabinets to avoid going hungry. He never had to fight for his life in High School, nor ever got kicked out of one. I’m certain he never dodged bullets for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, or had to outrun security for eating supermarket food with no intention of paying. But I did.

I got free haircuts in project hallways, drank out of open fire hydrants when thirsty and regularly walked miles because I couldn’t afford public transportation. All I’ve ever known was survival. I mastered the art of “getting by,” all the while scraping the bottom of the socioeconomic pool searching for reasons to live, let alone, be grateful. I honestly didn’t think I was going to make it past the age of 25.

Once, I shielded horrified neighbors from watching a teen bleed out to death from multiple stab wounds—ignoring that I just met him minutes before and his killer lived across the street from me.

Growing up on the streets of New York, I learned how to fight at a young age. I trained in various martial arts under some of the original Guardian Angel gang members and would go on patrol with Curtis Sliwa. We were tough, life would prove to be tougher.

Lin’s mom is an accomplished Doctor of Psychology; Mine pretends to be one of theology. One time, my mom even attempted to perform an exorcism on me because she was too ignorant to know I was stimming from Aspergers. On another occasion, she caught me masturbating when I was 9 years old and thought it necessary to drag me naked into the living room and have my dad preach to me while I sat there with a bible on my lap. As you can imagine, the humiliation was devastating and long-lasting.

As for my dad, his career was variations of custodial work—which I considered more laudable. He taught me how to manage and maintain a building, do handyman work, and deal with entitled tenants. Lin’s dad has a prestigious career decorated with political and community leadership, service and entrepreneurship, among other things. HBO even produced a documentary about his extraordinary life and accomplishments. My mom told me she felt like a failed parent because I wanted to study film and acting instead of becoming a pastor. My dad mocked me for modeling, believing that a real man worked 12-hour days hard labor. I wanted to please him, so I tried it. But there was a moment while standing on the roof of some Brooklyn brownstone in the freezing rain—earning less than minimum wage and working alongside illegal immigrants—that I knew this wasn’t the future for me. No dad, I’m not joining the military like you had hoped.

It wouldn’t be until I was much older when my parents opened up about their arduous beginnings. I assume it was their way of shielding my siblings and I from the harsh realities of life. Unfortunately, we missed out on a slew of insights and truths our strict religious upbringing could never offer. Parents try to be perfect for their children, I get that. My mom was a desperate teenager looking for a way out of a broken abusive home and my dad was a local bouncer fresh out the Navy with no aspirations. They were simply figuring out how to get by. And it ultimately became my inheritance. However, I cannot blame or judge them; They did the best they knew how and I eternally love and respect them for it.

I had unforgettable moments with seldom extraordinary women throughout my life. They powered me through tough stretches. I pieced together their beautiful essences, pass my destitution, to keep myself from falling apart. Photographed by Jubei Raziel

Here I am, pretending to be a graduate from Columbia University. I might actually fit the bill too. Broke, well-spoken and uniquely educated, no children, completely healthy, and a great credit score. I also have no history with drugs or alcohol, no criminal record, or debt, and now, I’m working on a novel. On the surface, one may think I’m on the fast track to success. The truth is, I died getting here. I had to. Death became necessary in order for me to live.

You see, I may not have been able to change my upbringing or vast challenges, but I could evolve who i was and how I progressed. And I did.

I finish the macadamia nut cookie I grabbed earlier for dessert and chuckle at where I am. If only my childhood friends could see me now. Too bad many of them are dead or in prison. Columbia University is an incredible school. Alas, what might’ve been will never be for me. I sincerely wish everyone here who graduated the very best. They have no idea how good they have it.

When the event concludes, I leave with renewed vigor. I’ve come a long way. And the thirst for more in life hasn’t diminished. I still burn inside. But can I pull-off something more than pretending to be a Columbia graduate?

Photographed by Jubei Raziel

While heading home, I walk pass the United Palace Theater where an image of Lin-Manuel Miranda standing on stage is displayed outside alongside others. Underneath it, a homeless person sleeps. A couple blocks later, I see Galicia, a Spanish restaurant that closed its business for good. I’m reminded of the time when I was there eating while Lin and his dad were just three blocks away celebrating with the media over their successful efforts of keeping Coogans — a local Irish pub — open. Galicia was a neighborhood favorite and staple since the 1980’s. It faced the identical problem Coogans had (steep rent increase), but celebrities and politicians didn’t eat at Galicia, so, no dice. I miss that place. Affordable Spanish food has become increasingly difficult to find in Washington Heights. (Note that Coogans permanently closed in 2020 regardless.)

At this point, you may recognize the idiosyncratic dichotomy between Lin-Manuel and myself. We lived in two different New Yorks as neighbors. Nonetheless, I’m left wondering if it's possible to change my circumstances, or, if I’m damned by the gods. Is there untold wisdom, or trade secrets I can learn from my neighbor? Could his path to success be imitated somehow? In short, no.

Everyone wants to be the exception, unique, extraordinary. Unfortunately, this isn’t achieved, decided, nor willed by those seeking it. The “exception” is a statistical probability that only increases with support, sacrifice, and good old-fashion elbow grease. Otherwise, determined entirely by timing and flat-out luck.

Many of you have incredible stories to tell. The journey in figuring out how might end up being greater than the one you originally sought out to tell.

If everyone is special, then no one is. Lin-Manuel’s journey to wealth and fame is exclusive to him and cannot be replicated. Furthermore, there isn’t much to extrapolate from his career or life that could be a boon to me. My version of In the Heights would’ve gone down as the most violent crime saga in Broadway history. Hamilton? He was a Puerto Rican friend of mine who lived in a basement on 181st street. We trained martial arts in his living room in the dark because he couldn’t afford electricity.

Whilst Lin grew up privileged, I learned the value of a buck collecting bottles and cans out of trash bins so I could recycle them for enough money to buy firecrackers from the corner bodega for the 4th of July. I shined shoes and sold my own toys for ice cream. I hobbled miles home on crutches from the hospital at 2 A.M. because my dad refused to pick me up. I stood on welfare lines with my mom for food, and during summers, went to public schools for free city meals. This was my life. What can I possibly learn from Lin? Positive thinking? I’m not naive enough.

Evidently, Luis and Luz-Towns Miranda provided their children with all the essentials necessary to achieve in life; They proudly remain a close-knit family. Mine? We’re just five individuals connected by DNA, something I suspect many others fall under but hold in discretion. But what does this mean in terms of my probability for success? Well, unfortunately, I don’t live in a meritocratic society, otherwise, I’d already be successful and well-off. Nepotism? I wish. All of this profoundly reveals that the single most critical element to one’s chances at success in life are their parent(s)...family.

For parents out there, nurturing your children, cultivating their interests, empowering their dreams and aspirations, and sacrificing for them are the greatest investments you could ever make. Even if your children’s ambitions are never realized, the journey and experiences along the way—in it of themselves—are worth it. It’s what gives life color, flavor, meaning and significance.

I wasn’t fortunate with this. As a result, the math merely worked itself out. Inadequate parenting stands as the singular and most influential reason why most of us will never break through our glass ceiling and become more in life. It only feels worse knowing there isn’t anything we can do about it. We don’t choose to be born, nor have the option of determining who our parents are, or, how, when or where we get to live. If that were the case, we’d all be legendary figures of history.

To the underprivileged: Be wary of the “rags to riches” stories that are widely advertised and celebrated in society. They never happen the way you think (Hard Work + Sacrifice = Recognition and Reward, is a lie). It requires a perfect storm of events for glorious success (including how you were raised). In no way am I suggesting that hard work, sacrifice and dedication aren’t necessary; they are. If anything, they may increase your probability for success. But their value and reward are often found in personal evolution, not in a career or bank account.

Many of you have incredible stories and creations to share with the world. The journey in figuring out how often ends up being greater than what you anticipated. I have no illusions of becoming “wildly successful” and grown content with this. No matter how hard I work and sacrifice, I cannot will reality and results to my desires. There are limited opportunities, steep competition, gatekeepers, unforeseen calamities, timing, and unanticipated difficulties that occur and exist. Nevertheless, I have to believe and live like I can. Simply because that’s my responsibility; to—against all odds—create and wield my voice through the craft of storytelling. Sure, a healthy dose of divine positivity goes a long way, but I’m not blind to the fact I’m another underprivileged child of immigrant parents prostituting out their harrowing tale to invoke affinity towards consideration.

The most critical factors yet remain: Without a loving family, healthy support system, and a strong network, your chances of success are implausible, nil. You may learn how to survive and adapt to the terrain like I did, but it’s probable you’ll never reach that highland. Feel free to read every self-help book in the world, it won’t change this harsh reality.

Photographed by Jubei Raziel

Peter Dinklage gave a commencement speech in 2012 at Bennington College, revealing that the friendships you have growing up, the network of people surrounding you when you graduate college, the loved ones who support and champion you, are likely the catalyst to any success you might find in life. Relationships are everything. Understand that talent and skill will always be overshadowed by this.

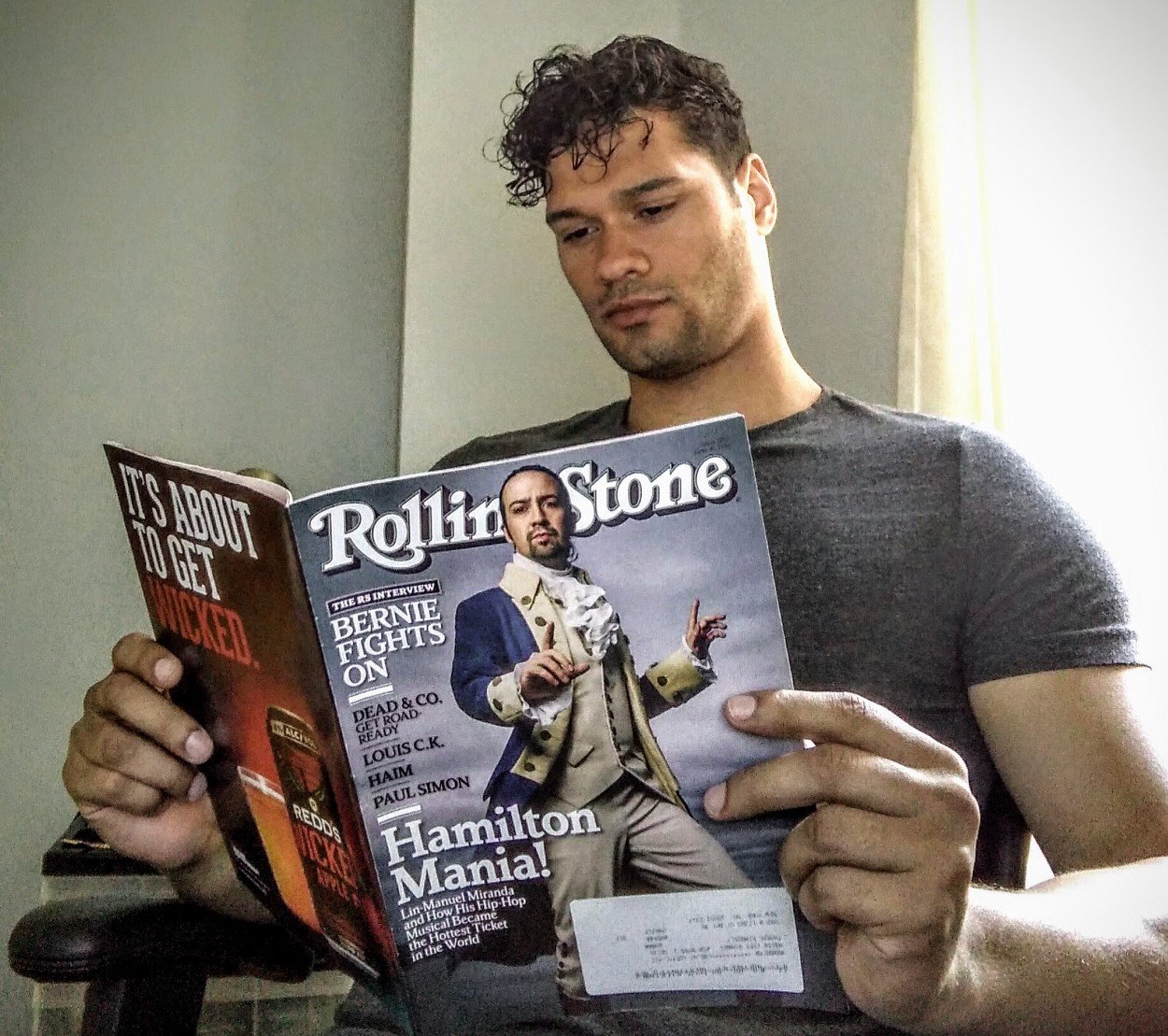

What has become an enduring haunting of mine is a song Lin-Manuel Miranda created with Nas, Dave East and Aloe Blacc called, Wrote My Way Out. Its strong and clear message speaks to me more than I care to admit. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, writing has become my saving grace, sustaining me through long unemployment, curfews, mandates, riots and lock-downs. And even though Lin-Manuel and his dad would go on to unfollow me on Twitter, I’ve grown to appreciate the time they did.

I may move through life with a New York edge, but I carry an honesty forged by fire. I’ve given everything just to breathe. And there’s no light at the end of the tunnel. I am the light. There’s no situation or curse I haven’t endured, and there will be no breaks. You shouldn’t expect any either. Especially if you lack the critical foundation needed just to have a standing chance. Dreams are for those asleep, not for those striving. I’m going to write my way out, Lin. I’ll die trying.

Self-portrait of myself sitting along the Hudson.

For those who are reading this, your journey may not be all that different. You will be accused of not working hard enough, of not sacrificing enough, of not being good enough. You’ll feel suppressed by the gatekeepers of the world, and grow weary at the lack of opportunity, or at the overwhelming competition. Life is harsh and it will continue without you. Pushing for dreams against reality will either recreate you or crush you. But you get to decided which it will be. And this is what will separate you from everyone else.

Remain constructive no matter what. Fall in love with the process of productivity, with the nuances of a laborious life. Forget about results and the successes of others, and you will discover something profound: You’re alive, living with conviction and passion. Tomorrow doesn’t matter as much as today. Stay present. Be mindful. It’s okay to fantasize and take breaks. It’s okay to be angry and depressed. Stay productive; It will become your weapon and protect you through the long night. Realize that the journey is the reward.

In the end, whether or not I ever connect with Lin-Manuel Miranda or share a similar success isn’t the objective. I must battle, and so must you. Nothing of value, nothing worth remembering or lasts for generations has ever emerged without conflict, contention or resistance. Embrace them. It’s the only path to becoming legend. Pain, sacrifice, darkness, suffering, and their minions are the very guts of quality, significance and beauty. Never give up.

The goal is not to become extraordinary, but to create something that is. Live well. Die strong.